It has been awhile since I last made an entry into this blog. The issue of climate change has become one of extreme importance. The Copenhagen Conference needs to succeed in setting some real topics. The official web-site for the conference is

for those who are interested. The news from the Arctic continues to be alarming. Although the winter of 2008-2009 was back to more usual levels of cold, this past summer has seen what may well be the last of the multi-year ice in the Beaufort Sea. This means only thinner annual ice will remain each winter and may well completely melt during future summers. The habitats of polar bears, walrus, seals and other marine mammals in the High Arctic are significantly under threat. The Northwest Passage was completely ice-free in 2007 for the first time in history. Greenland glacial melt is continuing to increase threatening rising sea levels and interference with the Gulf Stream warming northwest Europe. Inuit hunters and elders are continuing to sound the alarm. The people of Nunaat [Inuit land and ice all around the Arctic] are trying to get us all to listen. The Inuit Circumpolar Conference released the following in April of 2009:

A Circumpolar Inuit Declaration on Sovereignty in the Arctic

We, the Inuit of Inuit Nunaat, declare as follows:

1. Inuit and the Arctic

1.1 Inuit live in the Arctic. Inuit live in the vast, circumpolar region of land, sea and ice known as the Arctic. We depend on the marine and terrestrial plants and animals supported by the coastal zones of the Arctic Ocean, the tundra and the sea ice. The Arctic is our home.

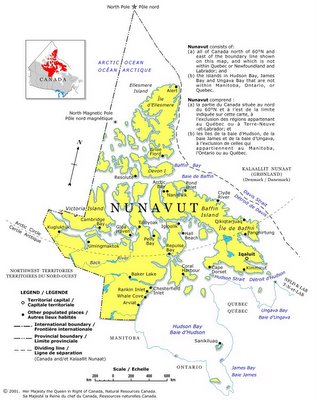

1.2 Inuit have been living in the Arctic from time immemorial. From time immemorial, Inuit have been living in the Arctic. Our home in the circumpolar world, Inuit Nunaat, stretches from Greenland to Canada, Alaska and the coastal regions of Chukotka, Russia. Our use and occupation of Arctic lands and waters pre-dates recorded history. Our unique knowledge, experience of the Arctic, and language are the foundation of our way of life and culture.

1.3 Inuit are a people. Though Inuit live across a far-reaching circumpolar region, we are united as a single people. Our sense of unity is fostered and celebrated by the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), which represents the Inuit of Denmark/Greenland, Canada, USA and Russia. As a people, we enjoy the rights of all peoples. These include the rights recognized in and by various international instruments and institutions, such as the Charter of the United Nations; the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action; the Human Rights Council; the Arctic Council; and the Organization of American States.

1.4 Inuit are an indigenous people. Inuit are an indigenous people with the rights and responsibilities of all indigenous peoples. These include the rights recognized in and by international legal and political instruments and bodies, such as the recommendations of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, the UN Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the 2007 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and others.

Central to our rights as a people is the right to self-determination. It is our right to freely determine our political status, freely pursue our economic, social, cultural and linguistic development, and freely dispose of our natural wealth and resources. States are obligated to respect and promote the realization of our right to self-determination. (See, for example, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [ICCPR], Art. 1.)

Our rights as an indigenous people include the following rights recognized in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), all of which are relevant to sovereignty and sovereign rights in the Arctic: the right to self-determination, to freely determine our political status and to freely pursue our economic, social and cultural, including linguistic, development (Art. 3); the right to internal autonomy or self-government (Art. 4); the right to recognition, observance and enforcement of treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements concluded with states (Art. 37); the right to maintain and strengthen our distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions, while retaining the right to participate fully in the political, economic, social and cultural life of states (Art. 5); the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect our rights and to maintain and develop our own indigenous decision-making institutions (Art. 18); the right to own, use, develop and control our lands, territories and resources and the right to ensure that no project affecting our lands, territories or resources will proceed without our free and informed consent (Art. 25-32); the right to peace and security (Art. 7); and the right to conservation and protection of our environment (Art. 29).

1.5 Inuit are an indigenous people of the Arctic. Our status, rights and responsibilities as a people among the peoples of the world, and as an indigenous people, are exercised within the unique geographic, environmental, cultural and political context of the Arctic. This has been acknowledged in the eight-nation Arctic Council, which provides a direct, participatory role for Inuit through the permanent participant status accorded the Inuit Circumpolar Council (Art. 2).

1.6 Inuit are citizens of Arctic states. As citizens of Arctic states (Denmark, Canada, USA and Russia), we have the rights and responsibilities afforded all citizens under the constitutions, laws, policies and public sector programs of these states. These rights and responsibilities do not diminish the rights and responsibilities of Inuit as a people under international law.

1.7 Inuit are indigenous citizens of Arctic states. As an indigenous people within Arctic states, we have the rights and responsibilities afforded all indigenous peoples under the constitutions, laws, policies and public sector programs of these states. These rights and responsibilities do not diminish the rights and responsibilities of Inuit as a people under international law.

1.8 Inuit are indigenous citizens of each of the major political subunits of Arctic states (states, provinces, territories and regions). As an indigenous people within Arctic states, provinces, territories, regions or other political subunits, we have the rights and responsibilities afforded all indigenous peoples under the constitutions, laws, policies and public sector programs of these subunits. These rights and responsibilities do not diminish the rights and responsibilities of Inuit as a people under international law.

2. The Evolving Nature of Sovereignty in the Arctic

2.1 “Sovereignty” is a term that has often been used to refer to the absolute and independent authority of a community or nation both internally and externally. Sovereignty is a contested concept, however, and does not have a fixed meaning. Old ideas of sovereignty are breaking down as different governance models, such as the European Union, evolve. Sovereignties overlap and are frequently divided within federations in creative ways to recognize the right of peoples. For Inuit living within the states of Russia, Canada, the USA and Denmark/Greenland, issues of sovereignty and sovereign rights must be examined and assessed in the context of our long history of struggle to gain recognition and respect as an Arctic indigenous people having the right to exercise self-determination over our lives, territories, cultures and languages.

2.2 Recognition and respect for our right to self-determination is developing at varying paces and in various forms in the Arctic states in which we live. Following a referendum in November 2008, the areas of self-government in Greenland will expand greatly and, among other things, Greenlandic (Kalaallisut) will become Greenland’s sole official language. In Canada, four land claims agreements are some of the key building blocks of Inuit rights; while there are conflicts over the implementation of these agreements, they remain of vital relevance to matters of self-determination and of sovereignty and sovereign rights. In Alaska, much work is needed to clarify and implement the rights recognized in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). In particular, subsistence hunting and self-government rights need to be fully respected and accommodated, and issues impeding their enjoyment and implementation need to be addressed and resolved. And in Chukotka, Russia, a very limited number of administrative processes have begun to secure recognition of Inuit rights. These developments will provide a foundation on which to construct future, creative governance arrangements tailored to diverse circumstances in states, regions and communities.

2.3 In exercising our right to self-determination in the circumpolar Arctic, we continue to develop innovative and creative jurisdictional arrangements that will appropriately balance our rights and responsibilities as an indigenous people, the rights and responsibilities we share with other peoples who live among us, and the rights and responsibilities of states. In seeking to exercise our rights in the Arctic, we continue to promote compromise and harmony with and among our neighbours.

2.4 International and other instruments increasingly recognize the rights of indigenous peoples to self-determination and representation in intergovernmental matters, and are evolving beyond issues of internal governance to external relations. (See, for example: ICCPR, Art. 1; UNDRIP, Art. 3; Draft Nordic Saami Convention, Art. 17, 19; Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, Art. 5.9).

2.5 Inuit are permanent participants at the Arctic Council with a direct and meaningful seat at discussion and negotiating tables (See 1997 Ottawa Declaration on the Establishment of the Arctic Council).

2.6 In spite of a recognition by the five coastal Arctic states (Norway, Denmark, Canada, USA and Russia) of the need to use international mechanisms and international law to resolve sovereignty disputes (see 2008 Ilulissat Declaration), these states, in their discussions of Arctic sovereignty, have not referenced existing international instruments that promote and protect the rights of indigenous peoples. They have also neglected to include Inuit in Arctic sovereignty discussions in a manner comparable to Arctic Council deliberations.

3. Inuit, the Arctic and Sovereignty: Looking Forward

The foundations of action

3.1 The actions of Arctic peoples and states, the interactions between them, and the conduct of international relations must be anchored in the rule of law.

3.2 The actions of Arctic peoples and states, the interactions between them, and the conduct of international relations must give primary respect to the need for global environmental security, the need for peaceful resolution of disputes, and the inextricable linkages between issues of sovereignty and sovereign rights in the Arctic and issues of self-determination.

Inuit as active partners

3.3 The inextricable linkages between issues of sovereignty and sovereign rights in the Arctic and Inuit self-determination and other rights require states to accept the presence and role of Inuit as partners in the conduct of international relations in the Arctic.

3.4 A variety of other factors, ranging from unique Inuit knowledge of Arctic ecosystems to the need for appropriate emphasis on sustainability in the weighing of resource development proposals, provide practical advantages to conducting international relations in the Arctic in partnership with Inuit.

3.5 Inuit consent, expertise and perspectives are critical to progress on international issues involving the Arctic, such as global environmental security, sustainable development, militarization, commercial fishing, shipping, human health, and economic and social development.

3.6 As states increasingly focus on the Arctic and its resources, and as climate change continues to create easier access to the Arctic, Inuit inclusion as active partners is central to all national and international deliberations on Arctic sovereignty and related questions, such as who owns the Arctic, who has the right to traverse the Arctic, who has the right to develop the Arctic, and who will be responsible for the social and environmental impacts increasingly facing the Arctic. We have unique knowledge and experience to bring to these deliberations. The inclusion of Inuit as active partners in all future deliberations on Arctic sovereignty will benefit both the Inuit community and the international community.

3.7 The extensive involvement of Inuit in global, trans-national and indigenous politics requires the building of new partnerships with states for the protection and promotion of indigenous economies, cultures and traditions. Partnerships must acknowledge that industrial development of the natural resource wealth of the Arctic can proceed only insofar as it enhances the economic and social well-being of Inuit and safeguards our environmental security.

The need for global cooperation

3.8 There is a pressing need for enhanced international exchange and cooperation in relation to the Arctic, particularly in relation to the dynamics and impacts of climate change and sustainable economic and social development. Regional institutions that draw together Arctic states, states from outside the Arctic, and representatives of Arctic indigenous peoples can provide useful mechanisms for international exchange and cooperation.

3.9 The pursuit of global environmental security requires a coordinated global approach to the challenges of climate change, a rigorous plan to arrest the growth in human-generated carbon emissions, and a far-reaching program of adaptation to climate change in Arctic regions and communities.

3.10 The magnitude of the climate change problem dictates that Arctic states and their peoples fully participate in international efforts aimed at arresting and reversing levels of greenhouse gas emissions and enter into international protocols and treaties. These international efforts, protocols and treaties cannot be successful without the full participation and cooperation of indigenous peoples.

Healthy Arctic communities

3.11 In the pursuit of economic opportunities in a warming Arctic, states must act so as to: (1) put economic activity on a sustainable footing; (2) avoid harmful resource exploitation; (3) achieve standards of living for Inuit that meet national and international norms and minimums; and (4) deflect sudden and far-reaching demographic shifts that would overwhelm and marginalize indigenous peoples where we are rooted and have endured.

3.12 The foundation, projection and enjoyment of Arctic sovereignty and sovereign rights all require healthy and sustainable communities in the Arctic. In this sense, “sovereignty begins at home.”

Building on today’s mechanisms for the future

3.13 We will exercise our rights of self-determination in the Arctic by building on institutions such as the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the Arctic Council, the Arctic-specific features of international instruments, such as the ice-covered-waters provision of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and the Arctic-related work of international mechanisms, such as the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, the office of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous Peoples, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

4. A Circumpolar Inuit Declaration on Sovereignty in the Arctic

4.1 At the first Inuit Leaders’ Summit, 6-7 November 2008, in Kuujjuaq, Nunavik, Canada, Inuit leaders from Greenland, Canada and Alaska gathered to address Arctic sovereignty. On 7 November, International Inuit Day, we expressed unity in our concerns over Arctic sovereignty deliberations, examined the options for addressing these concerns, and strongly committed to developing a formal declaration on Arctic sovereignty. We also noted that the 2008 Ilulissat Declaration on Arctic sovereignty by ministers representing the five coastal Arctic states did not go far enough in affirming the rights Inuit have gained through international law, land claims and self-government processes.

4.2 The conduct of international relations in the Arctic and the resolution of international disputes in the Arctic are not the sole preserve of Arctic states or other states; they are also within the purview of the Arctic’s indigenous peoples. The development of international institutions in the Arctic, such as multi-level governance systems and indigenous peoples’ organizations, must transcend Arctic states’ agendas on sovereignty and sovereign rights and the traditional monopoly claimed by states in the area of foreign affairs.

4.3 Issues of sovereignty and sovereign rights in the Arctic have become inextricably linked to issues of self-determination in the Arctic. Inuit and Arctic states must, therefore, work together closely and constructively to chart the future of the Arctic.

We, the Inuit of Inuit Nunaat, are committed to this Declaration and to working with Arctic states and others to build partnerships in which the rights, roles and responsibilities of Inuit are fully recognized

and accommodated.